Designing your first multi-billion startup

In this post, I will describe an application designing process and the way I organize code in my Scala projects.

I will introduce you with one of my pet projects - release pager. We will go through the problem it solves, split the problem into smaller problems, define logical services and will take a look at how to organize the code. In the next chapters, I will cover more specific parts of the application and implementation details.

If you prefer code rather than text you are welcome to check the project page.

The problem to solve

When you work with open-source software… When you like to be on the edge of technology… When you like to live dangerously… When you want to raise your blood pressure and fill your veins with adrenaline you update your favorite software to the latest version whenever it comes out.

Assuming that you are using Scala and SBT you can adopt Scala Steward SBT plugin and it will help you to keep your dependencies up-to-date. However, if you are curious about releases of software that is not part of your project dependency list you need to look around for other ways of doing this. Most probably you are too lazy to press F5 every minute on a GitHub release page of that fancy project you like. You might even know at least a few other ways how to spend your free time. Also, some people say laziness is the engine of progress.

What are the alternatives? How about delegating this task to someone, who will enjoy it? Let’s write a bot, that will “press F5” for us!

What is the most convenient way to deliver a message nowadays?

People have different habits, but for me, online messaging is the most convenient way of doing it today.

However, on my mobile phone, there are at least 4 messaging apps. Currently, my favorite is Telegram.

I have stickers of my cat in Telegram. I hope you don’t need other arguments.

The solution

Breaking the problem into smaller parts

So far we know that we want to build a Telegram bot, which will connect to Telegram API and notify users about new versions of some software. Lets narrow this down and say the software should be publicly available on GitHub. Also, users should have the ability to select repositories they are interested in, so the bot should interact with user input. This bot should store a user-defined list of GitHub repositories and its latest versions. The bot would automatically check for new releases of these repositories. When a new repository version is released user should receive a notification if he has subscribed to this repository. Lets call this bot “release pager”.

Usually, I start with defining requirements and problem specification. Now we have specified a general idea of what we are trying to build. It’s always good to understand what issue you are trying to solve. Some people told me this principle also works outside of the IT world :).

The next task would be to split the “big” problem into several smaller problems. If you are lucky enough you will end up with a natural separation of logical services. At this point, I tend to avoid mentioning specific technologies, frameworks, and libraries. The focus should be on the problem itself, but the implementation details will come later.

Let’s see what steps we need to take in order to provide users with their needs.

- Communicate with users using Telegram

- Define user interaction scenarios

- Retrieve latest repository versions from GitHub

- Save the latest version of a GitHub repository

- Save the user-defined list of GitHub repositories

- Retrieve the user-defined list of GitHub repositories

- Validate user input

- Schedule new version retrieval

- Broadcast new version to subscribed users

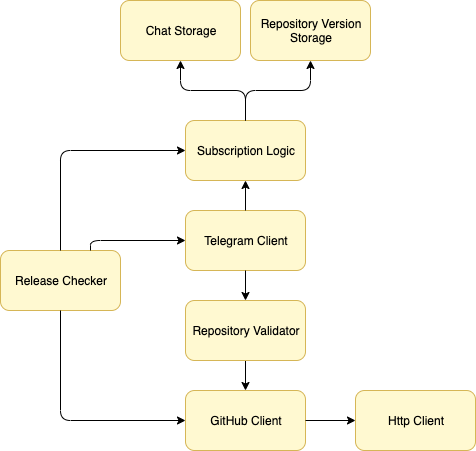

Looking at this list you can see that some of the functionality can be grouped together and form services.

This is a release pager service diagram. This diagram also visualizes dependencies between services. Here we check that we have divided our services into separate logical pieces. If at this stage you see cyclic dependencies it means you can break the services into smaller entities or you have grouped unrelated concepts together.

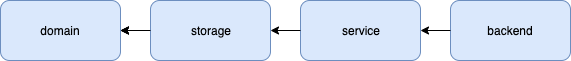

Before jumping into business logic implementation I start with structuring the application and specifically with defining SBT modules. Usually, I split SBT modules into technical layers. This gives me a simple directed module dependency graph. For instance, the domain model module will never know about any other modules (eg. storage), but the storage module will depend on the domain model module. As the service module depends on the storage module it will also depend on the domain module transitively.

The structure is very simple:

- Domain module contains all the models

- Storage module contains all the logic of saving and retrieving the data

- Service module contains all the business logic

- Backend module contains all the logic of starting the server

To be honest I feel that backend is not the best name for the module and maybe server would fit better.

If you have a suggestion for a better name, please put it in the comments.

In my SBT file, I define a project for every module.

lazy val service = project

.settings(commonSettings) // 1

.settings(libraryDependencies ++= serviceDependencies) // 2

.dependsOn(storage) // 3

In the code above we define module service, which will be created at the root of the project.

Below I will describe in detail what is going on using the numbered list (check numbers in the code comments above).

- Set common module settings

- Set

servicemodule library dependencies - Define dependency on the

storagemodule

For full module definition please check the build.sbt file.

Defining project packages

Separating your business logic into pieces makes maintainability, readability, and navigation through your code easier.

Refactoring is not a big deal if you have to replace a small building block in the code.

We already have defined one separation axis - technical layers. These layers are separated from each other using SBT project modules.

Let’s define the second separation axis - business logic. This can be done with packages.

As we are splitting the application technical layers using SBT modules, I would not recommend creating packages like service, repository etc.

Of course, this applies only if it is not a part of your business domain. In this project, packages are used exclusively for business logic modularisation.

Good:

- io.pager.subscription

- io.pager.lookup

Bad:

- io.pager.service

- io.pager.repository

So let’s say I have a service called SubscriptionLogic, I have a domain model Subscription,

then I would expect them to be members of the subscription package, in 2 different SBT modules (service and domain accordingly).

If at some point there will be a necessity to extract subscription service into a separate microservice we can go through all modules and extract the package.

If I will decide to add another lookup source, I would create 2 separate SBT modules. For example, github-service and gitlab-service.

Then all the common code would be moved to the common-service module and all source-specific logic (eg. validation) would stay in a specific source SBT module.

Note: module and package structure might be quite controversial and I’m still experimenting with it.

Design your service interfaces

Usually, I start with drafting logical service interfaces or in Tagless Final terms - defining algebras.

Dependent services will always call interface methods, so whenever you make changes in the implementation of a method of serviceA,

it is important that dependent serviceB won’t even know about these changes.

Lets put it even more strict - you should never care about the implementation details of a service that you call.

That is why I would advise designing all the services against interfaces (or algebras). This will come handy in unit testing.

Also, if you use pure functions you do not expect any side effects in a method before we run the returned effect.

This also simplifies unit testing and improves behavior predictability of your applications.

Services should act as black boxes with clear API. There are plenty of good guidelines on clean API design, so I won’t go into detail. If you provide external API to other systems, then your API might be a critical part of the system and I would recommend design it thoroughly. In the release-pager, there is no external API, so it is out of the scope of this article.

Even though I promised I won’t go into interface design details, I want to give few small Scala service interface design tips, which might be handy.

Types are your friends. Don’t be lazy and use types. More types! Types, types, types!

def distance(velocity: BigDecimal, time: BigDecimal): BigDecimal // bad

def distance(velocity: Velocity, time: Time): Distance // good

It’s easy to make a mistake and mix up velocity and time on the caller side in the first example.

In this particular example, it doesn’t matter as most probably this function will only perform multiplication, which is commutative function.

If your function is more sophisticated it might lead to a bug.

Sometimes it is not that easy to catch such a bug with tests.

That’s assuming you have tests, of course.

There are different approaches to tackle this: Value classes, NewTypes, Tagging and others.

Off-topic: in one of my projects I took it to the max and while Opaque types are not available in Scala, I’ve implemented specific methods in my value classes:

case class Velocity(value: BigDecimal) extends AnyVal {

def *(time: Time): Distance = time.value * value

}

Here the math is covered with types. Whenever you multiply velocity on time you automatically have distance type as the result. This approach has it’s pros and cons and in my specific case advantage list was bigger.

Also, I would recommend you to avoid passing Monadic types as single arguments in your methods.

def find(id: Option[FooId]): Option[Foo] // bad

def find(id: FooId): Option[Foo] // good

The interface of your service should know how to retrieve an entity by id. Absence of the id should be handled on the client side. This makes testing of the interface much easier. If in your case you can have an optional id, I would split it into 2 separate methods: “find by id” and “default value”. The latter doesn’t need any parameters.

Summary

In this article, we have defined a specific problem we want to solve with coding. We have recognized all the dependencies on external services.

One of the important things in application design is to split the big problem into a set of smaller problems, that can be tackled individually.

I have shared my recommendations in code organisation when building the foundation of an application.

As the last bit, I have given several tips on service interface design.

In the next chapter, I will go into implementation details and show you the actual implementation of the release pager. Tune in!