![Implement your future with ZIO [RC17 edition]](/assets/img/welcome-zio/my-pager.png)

Implement your future with ZIO [RC17 edition]

This post will help you to start building Scala applications with ZIO.

Today there are lots of libraries in Scala ecosystem, which promise to improve your efficiency. I wrote this post in order to help you to start with the new effect type on the block - ZIO. It is a huge library that provides you powerful tools to build concurrent applications and its own ecosystem.

This post doesn’t cover all the functionality but will help you get started with something bigger than a ‘Hello World’ app. On certain topics, I will not go into the details, but rather provide links to allow you to do your own research. The intent of this post is to familiarize you with the library on a high level. In the next chapters, I would like to cover more specific parts of ZIO ecosystem and guide you in a deep dive into the different parts of the library.

Warning! This blog post is outdated and is based on an old ZIO version 1.0.0-RC17.

Please check out the updated post with the new ZIO features.

Please note that we will be using ZIO version 1.0.0-RC17.

We should expect to see ZIO API changes in the next release candidate (which will be the last before the official release).

If you would like to read an article based on version 1.0.0-RC18 - click here.

If you prefer reading code rather than text you are welcome to check the project page.

The problem to solve

We look for tools that solve our problems and we should not look for problems to solve with our beloved tools. Otherwise, we end up with a zoo of different technologies that is not sustainable.

In the previous article we have defined a problem that needs to be solved. If you haven’t read it yet, I would recommend checking it before you proceed with this one.

Scala ecosystem is diverse and can provide you with various different approaches and techniques that can solve the very same business problem. There are different approaches and frameworks to build applications. ZIO is one of the newest libraries in the ecosystem and is advertised as a library, that can simplify software development with Scala, which would make its users more efficient. As I like to explore the world of functional programming I decided to try it out and share my experience with you.

According to documentation ZIO is a library for asynchronous and concurrent programming that promotes pure functional programming. If functional programming is something you like or you feel interested in it, this should spark some curiosity in you.

Let’s take a look at what ZIO is about. ZIO allows you to build your programs in a “lazy” fashion. You describe how your program should behave in pure functions. These functions return data structures that are called functional effects. In short, a functional effect is an immutable value that describes tasks that should be done. When we create such an effect we have to run it manually. This means that all side-effects inside of the functional effect will be called only when we run it. You combine these effects into a program, which you run only once, on the very top level. If you are not familiar with this concept I would recommend you watching this presentation.

Functional effects make unit testing of side-effects quite easy. This will be covered in detail in one of the upcoming articles. For now, it’s important to mention, that ZIO has its own testing framework to test functional effects.

ZIO has tools to build low-level concurrency constructs. The library has its own implementation of fibers.

Fibers can be treated as lightweight “green threads”. They have low memory overhead, dynamic stacks and are garbage collected when they are not needed anymore.

There is a set of high-level operations built on top of fibers and it is recommended to use these operations when writing high-level business code.

The library has resource management features that provide strong guarantees of finalization and clean up.

Even if the processing of a resource data fails, ZIO guarantees to perform resource clean up to avoid memory leaks.

It is similar to try/catch block but expressed as a functional effect.

Also, there is its own implementation of the streaming model. Unfortunately, I haven’t looked closely into it yet.

ZIO can help you to handle dependency injection in your project. Usually, I don’t use any dependency injection frameworks in Scala.

Here we will have all the services initialized in the Main class and passed to dependent services via class constructors.

With ZIO the approach is a bit similar, but not exactly the same.

You instantiate your services in the Main class, but you don’t need to pass services to each other.

Sorry for spoilers, you will see how to wire up the dependencies later in this article.

The solution

Getting started with ZIO

In the previous article we have defined logical services that we have to implement. Now we have to implement them.

To structure the application services we will use module pattern.

If you have visited the module pattern link above, you saw that service definitions have environment type parameter - Service[R]. It is useful in testing and will be covered in the next chapter.

Every module will be expressed as a trait. Inside of this trait, we have a service definition, which we will have to implement.

It is recommended to use descriptive names in the service definition to avoid name clashes.

We will create instances of the service dependency tree at the very top level in Main class and the compiler won’t allow having name collisions.

All the dependencies will be checked at the compile time. Unfortunately, using module pattern do not guard you against having circular dependencies.

Having circular dependencies is a clear sign of bad service design which can be solved by separation of concerns.

On the very top level, you select specific implementations of the dependencies. We’ll see it later when will go through the Main class.

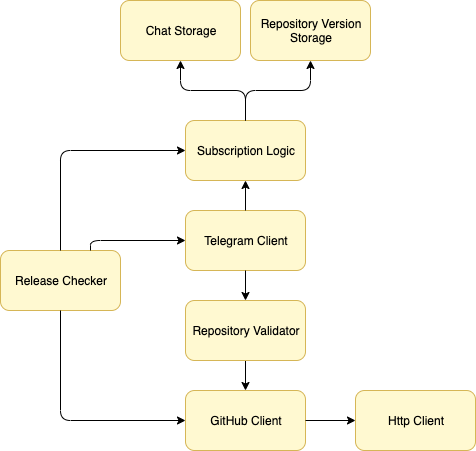

As you could see in the service diagram the heart of the application is subscription service. It should know how to store user subscriptions, repository versions and also how to retrieve them. Let’s define the subscription logic module:

trait SubscriptionLogic {

def subscription: SubscriptionLogic.Service

}

Here we have defined SubscriptionLogic module, which has subscription service definition.

In the current version of ZIO docs service definition uses val instead of def, but I prefer the latter.

Having def is the most abstract way to define a value inside of a trait. You can override it with def, val, lazy val or object.

With val you are limiting the options.

Implementation of the above definition is to be placed in the companion object.

object SubscriptionLogic {

trait Service {

def subscribe(chatId: ChatId, name: Name): Task[Unit]

def unsubscribe(chatId: ChatId, name: Name): Task[Unit]

def updateVersions(updatedVersions: Map[Name, Version]): Task[Unit]

def listSubscriptions(chatId: ChatId): Task[Set[Name]]

def listRepositories: Task[Map[Name, Option[Version]]]

def listSubscribers(name: Name): Task[Set[ChatId]]

}

}

Above you can see the definition of the subscription service interface.

Here we have defined several actions that this service can handle.

All the methods return type is zio.Task. This is a type alias to ZIO[Any, Throwable, A].

If you already heard about ZIO[-R, +E, +A] data type you know that type arguments are:

- R - type of environment required by the effects

- E - error type

- A - return type

In this case, the environment type is not required, but there might be an exception thrown by the DB layer (eg. lost DB connection).

Usually, we would catch expected errors and wrap them into a typed error. Here to keep things simple lets have Throwable.

To implement the logic we have to override SubscriptionLogic trait.

There are two ways to organize your implementations: either put all implementations inside of the companion object or create a separate file in the same package.

The difference is that if you will have a service with several implementations it won’t be convenient to navigate in several thousands of lines of one file.

In this specific case, we have only one implementation and that is why we will implement this service inside of the companion object.

trait Live extends SubscriptionLogic {

def logger: Logger.Service

def chatStorage: ChatStorage.Service

def repositoryVersionStorage: RepositoryVersionStorage.Service

override val subscription: Service = new Service {

override def subscribe(chatId: ChatId, name: Name): Task[Unit] =

logger.info(s"$chatId subscribed to $name") *>

chatStorage.subscribe(chatId, name)

override def unsubscribe(chatId: ChatId, name: Name): Task[Unit] =

logger.info(s"$chatId unsubscribed from $name") *>

chatStorage.unsubscribe(chatId, name)

... // skipped the rest

Lets skip the whole implementation in this snippet, you should get the idea. You can find the full implementation on GitHub.

This SubscriptionLogic implementation has three dependencies: a logger, chat storage and repository version storage.

Other implementation of this logic might have a totally different set of dependencies or even have no dependencies at all.

We will skip Logger because actually, we shouldn’t write our own logger or with other words re-invent a bicycle and just use some ready-to-use library.

At the moment of writing ZIO-logging is in early development, so I decided to wait for it and wrote a simple logger myself.

In the code above we see the implementation of two functions, which log user action and call chat storage.

For those, who find function aliases unreadable or not familiar with them, *> or an “ice cream” as I call it, is just an alias to flatMap function, which drops the result of the previous computation.

Here subscription logic doesn’t have any clue how the storage will work and it should not change.

Note that I use the word storage for services, that know how to save the data. This name is quite abstract and doesn’t imply any implementation details.

Let’s as an example pick ChatStorage. I have created two versions of the storage and one of them is not using a database, it is in-memory. Take a look:

trait ChatStorage {

def chatStorage: ChatStorage.Service

}

object ChatStorage {

type SubscriptionMap = Map[ChatId, Set[Name]]

trait Service {

def listSubscriptions(chatId: ChatId): Task[Set[Name]] // 1

def listSubscribers(name: Name): Task[Set[ChatId]] // 2

def subscribe(chatId: ChatId, name: Name): Task[Unit] // 3

def unsubscribe(chatId: ChatId, name: Name): Task[Unit] // 4

}

}

This is the definition of our storage logic.

- list all the subscriptions for a specific chat

- list all the subscribers for a specific repository

- add a new subscriber to a repository

- remove a subscriber from a repository

As we saw before there might be two or more implementations - we will have in-memory and SQL database versions.

In the scope of this article, we will use only the in-memory implementation. We create a Ref of a map and work with it.

Ref is a mutable reference to a value, which in this case is an immutable Map that stores all chat subscriptions (repository names).

ZIO takes care of the concurrent operations on Ref and guarantees the atomicity of all operations on the Map.

Here the requirements from the service are quite low - to be able to read the current state and update it when the user is changing his subscription list. Concurrently, of course.

trait InMemory extends ChatStorage {

def subscriptions: Ref[SubscriptionMap]

type RepositoryUpdate = Set[Name] => Set[Name]

val chatStorage: Service = new Service {

override def listSubscriptions(chatId: ChatId): UIO[Set[Name]] =

subscriptions

.get

.map(_.getOrElse(chatId, Set.empty)

override def listSubscribers(name: Name): UIO[Set[ChatId]] =

subscriptions

.get

.map(_.collect { case (chatId, repos) if repos.contains(name) => chatId }.toSet

override def subscribe(chatId: ChatId, name: Name): UIO[Unit] =

updateSubscriptions(chatId)(_ + name

override def unsubscribe(chatId: ChatId, name: Name): UIO[Unit] =

updateSubscriptions(chatId)(_ - name

private def updateSubscriptions(chatId: ChatId)(f: RepositoryUpdate): UIO[Unit] =

subscriptions.update { current =>

val subscriptions = current.getOrElse(chatId, Set.empty)

current + (chatId -> f(subscriptions))

}.unit

}

}

In this relatively small code snippet, a lot of stuff is happening.

As you might have noticed, the return type of all the methods is not Task as in the interface, but UIO.

UIO is used when you are sure that all the operations are pure and nothing can break.

ZIO can guarantee that operations on Ref are pure, but it has no control over your actions.

If you want to throw an exception inside of the update function - you can do it, the compiler does allow that. Should you do it? Never.

Writing code with functional effects requires attention and discipline. Also, it’s always great to have a code review afterward.

The difference between Task and UIO is that error type of UIO is Nothing instead of Throwable.

Having this we can expect that this function will not fail.

Updating the value inside Ref is simple. Just call update, take the provided state and change it.

That is why we have defined updateSubscriptions function, which gets the current value of Ref, finds user subscriptions and updates them with provided function.

So far we have only two functions - add and remove a subscription. The difference is in one sign: + in case of addition and - in case of deletion.

Reading the value is even simpler - you just need to call get on Ref and you have the current state.

Code looks clean and concise.

What if you have decided to implement a SQL table, which will store same data? You just create another implementation, for example Doobie:

trait Doobie extends ChatStorage {

def xa: Transactor[Task]

override val chatStorage: Service = new Service {

def listSubscriptions(chatId: ChatId): Task[Set[Name]] = ???

def listSubscribers(name: Name): Task[Set[ChatId]] = ???

def subscribe(chatId: ChatId, name: Name): Task[Unit] = ???

def unsubscribe(chatId: ChatId, name: Name): Task[Unit] = ???

}

}

Actual implementation is not important at this point, but you can see that now there is a different set of dependencies comparing to InMemory implementation.

We don’t need to have Ref as we will keep the values in a database. Now we have doobie.util.transactor.Transactor as the only dependency.

Now, if we want to replace InMemory implementation with Doobie implementation we have to do changes only in one place - the Main class where all the services are wired together.

As we design our services against interfaces we don’t care about implementation details of the dependee, so SubscriptionLogic implementations won’t be affected by the change.

Now we should have some basic understanding of how to build a business logic service with ZIO.

Wiring up

If you read so far, you’ve seen several service definitions and hopefully, you have a high level picture of what we are doing here. At this point, we could go through the rest of the service definition and implementation, but it’s not very different from what we’ve already seen except some small details. It would be interesting to see how we are starting the application and connect dependent services.

There are several ways to run a ZIO application.

- Build your program, create a custom

zio.RuntimecallunsafeRunon it and pass your program. - Extend your

Mainobject withzio.App. As we are building the application from scratch there is no good reason not to use the second approach.

Overriding the App forces also to override run method;

override def run(args: List[String]): ZIO[ZEnv, Nothing, Int]

As you can see, the program expects us to return a ZIO effect, which the library will run.

The first argument - ZEnv is default ZIO environment, that will provide you with:

-

Clock- access to system time, sleep function -

Console- access to the console (printing, reading input) -

System- access to environment variables -

Random- access to the randomizer -

Blocking- access to blocking thread pool

From this set of built-in services we will use:

-

Clock, to schedule GitHub repository latest version retrieval -

Console, for theConsoleLogger, to log stuff in stdout -

System, to retrieve environment variables

Let’s take a look at how the whole program looks like:

val program = for {

token <- telegramBotToken

subscriberMap <- Ref.make(Map.empty[Name, Option[Version]])

subscriptionMap <- Ref.make(Map.empty[ChatId, Set[Name]])

httpClient <- buildHttpClient

telegramClient <- buildTelegramClient(token)

_ <- buildProgram(subscriberMap, subscriptionMap, httpClient, telegramClient)

} yield ()

Here we prepare all the necessary inputs to build the program. As the first step, we retrieve Telegram bot token from environment variables.

Then we create 2 Ref instances holding empty Map for InMemory repositories. Then we build Http client and Telegram client.

These values are used to build the dependency tree.

ZIO gives you the ability to use services, that you don’t know how to instantiate or retrieve. It sounds like a dependency injection framework, right? At least for me, a dependency framework in Scala is something that is optional and not necessary needed. However, as ZIO will check all the dependencies at compile time you still are responsible for the dependency management.

How that works? Let’s take a look at the program itself:

val startTelegramClient = ZIO.accessM[TelegramClient](_.telegramClient.start).fork

val scheduleReleaseChecker =

ZIO

.accessM[ReleaseChecker with Clock](_.releaseChecker.scheduleRefresh)

.repeat(Schedule.fixed(Duration(1, TimeUnit.MINUTES)))

val program = startTelegramClient *> scheduleReleaseChecker

At the first line we access a TelegramClient, that will be provided later, call start method on it and fork into a separate Fiber.

As it was mentioned above, Fiber details are out of the scope of this article and will be covered in the next chapters.

For now, to keep things simple, imagine that we have spawned separate thread for it (it is not exactly correct, but you should get the point).

Then we access some environment that has ReleaseChecker and zio.Clock.

The first is needed to call a scheduleRefresh function, which will go to GitHub API and will check for new repository versions.

Second is needed to repeat the refresh effect every minute. In case of an error repeating will stop.

We combine both effects using the “ice cream” (flatMap) method and now we have one program, which environment is ReleaseChecker with Clock with TelegramClient.

The very last thing is to provide these missing services to the library and we are done.

We have to fulfill all the dependency requirements of the services we defined before.

For example, implementation of ReleaseChecker depends on SubscriptionLogic and the compiler expects it’s implementation to be provided.

At the end whole block of dependencies looks like this:

new TelegramClient.Canoe

with ScenarioLogic.CanoeScenarios

with Clock.Live

with Logger.Console

with Console.Live

with SubscriptionLogic.Live

with ChatStorage.InMemory

with RepositoryVersionStorage.InMemory

with RepositoryValidator.GitHub

with GitHubClient.Live

with HttpClient.Http4s

with ReleaseChecker.Live {

override def subscribers: Ref[SubscriberMap] = subscriberMap

override def subscriptions: Ref[SubscriptionMap] = subscriptionMap

override def client: Client[Task] = httpClient

override implicit def canoeClient: CanoeClient[Task] = telegramClient

}

The list is relatively long for such a small app. This is because we split services into smaller pieces that are easier to manage.

You can see the whole Main class here.

Instead of own implementations of the logger and HTTP client, we should have used some ready solution.

At the time of writing, ZIO-logging and ZIO-http are in early development, so I decided not to use them.

Also, most probably there is some working GitHub API client Scala wrapper, but for our needs (checking the last repository version) adding a new dependency could be a bit too much.

Summary

I’m happy if you have read until this point. This is my very first blog post and I would like to start a blog post series with it. As this is really a high-level introduction to ZIO capabilities this article doesn’t focus on specific things, it doesn’t compare ZIO with other solutions.

I have introduced you to ZIO. You are not close friends yet, but we’ll get there eventually. We have seen how to design and implement several services. We have seen how to build dependencies between these services. Also, we’ve used ZIO environment to create service instances and start the program. Without noticing we were actively using Fibers, which is the smallest concurrency element in ZIO.

As you may have noted we did not use Environment “hole” too much so far. It will change in the next chapter of the article series about unit testing.

How do I feel about ZIO? Excited, maybe. It took me a while to find the best way of doing dependency injection. Initially, I thought it would be a good idea to use the environment everywhere, but I ended up with implementation details leaking to other services via transitive dependencies. As now we are using the release candidate version of ZIO we should understand all the risks of developing an application in such an environment. It means API can change and there might be dependency incompatibilities in the future. There might be libraries, which are slower to move to newer versions.

However, according to conversations in ZIO discord it seems that 1.0.0 release is coming really soon and will bring some stability.

Would I recommend ZIO? It depends.

It depends on what you are trying to build.

If you want to learn something new or want to be aware of the trends in Scala world - use it.

If you are building your own multi-billion startup which won’t go live next Tuesday I would go for it.

If you are building some general-purpose library, which would not be a part of ZIO ecosystem? Emm, yes. Why I’m not so sure?

There are still people who are afraid of ‘z’ in the library names.

Also there are pros and cons to use Tagless Final style for this purpose. Such a comparison deserves a separate article.

Of course, you can use ZIO in your Tagless Final services as the effect type.

If your team is not very proficient with trendy functional programming terms like EJB, inheritance “effect”, “Tagless Final”, it might be challenging.

That, of course, depends on people, their ability and will to learn, project requirements and deadlines.

Functional programming requires attention, discipline and understanding of the things you do (that applies to any kind of programming, tho).

However, If you are familiar with Cats Effect, ZIO shouldn’t be hard for you. Lots of concepts are similar, just some method names might differ.

ZIO provides a lot of convenience methods, e.g. foldM and repeat we saw before.

These methods are quite useful and make your code easier to read and reduces amounts of boilerplate.

However, you have to get used to them, but I believe it is easier than get used to symbolic aliases.

It might be challenging to handle missing dependencies in big dependency trees as error messages provided by the compiler are quite long. Instead of having a diff you have the intersection of the expected and actual set of services. Example:

[error] /Users/psisojevs/projects/release-pager/backend/src/main/scala/io/pager/Main.scala:89:11: type mismatch;

[error] found : io.pager.client.telegram.TelegramClient.Canoe with io.pager.client.telegram.ScenarioLogic.CanoeScenarios with io.pager.logging.Logger.Console with zio.console.Console.Live with io.pager.subscription.SubscriptionLogic.Live with io.pager.subscription.ChatStorage.InMemory with io.pager.subscription.RepositoryVersionStorage.InMemory with io.pager.validation.RepositoryValidator.GitHub with io.pager.client.github.GitHubClient.Live with io.pager.client.http.HttpClient.Http4s with io.pager.lookup.ReleaseChecker.Live

[error] required: io.pager.client.telegram.TelegramClient with io.pager.lookup.ReleaseChecker with zio.clock.Clock

Here, the missing part is Clock service and this is not obvious from the first sight. I doubt it can be easily fixed by ZIO community.

However, you could reduce amounts of such error messages by grouping your services into smaller dependency trees.

I will continue exploring ZIO and the next parts of this article series will share my experience with error handling, unit testing possibilities and streams. Follow me on Twitter if you would like to be notified about new releases.