Effective testing with ZIO Test

This article will help you to effectively test your “effectful” ZIO code.

In the previous article we were exploring ZIO.

We’ve built the release pager application but we have skipped something very important - unit tests.

In this article, we will continue to develop the application. This time the target is to create unit tests for it.

Full versions of the code snippets I will use in this article are available on GitHub.

If for some reason you are interested in ZIO version 1.0.0-RC17 you are welcome to read first edition of this post.

ZIO has its own ecosystem and provides developer tools to increase development efficiency. One of the things which are included in the ZIO toolbox is ZIO Test framework. ZIO Test is designed for “effectful” testing.

The testing topic is broad and to stay specific we will not cover these questions:

- “What is ZIO?”

- “What are effects?”

- “What is unit testing?”

- “Why do we need unit tests?”

- “ZIO Test vs AngularJS”

Instead, let’s focus on:

- “How can we test effects with ZIO Test?”

- “How can we mock services with ZIO Test?”

- “How can we write property based tests with ZIO Test?”

- “What common issues we can have using ZIO Test for the first time?”

- “What are additional capabilities ZIO Test can provide?”

Getting started with ZIO Test

We start with adding test dependencies in Dependencies.scala:

val zioTest = "dev.zio" %% "zio-test" % Version.zio % "test"

val zioTestSbt = "dev.zio" %% "zio-test-sbt" % Version.zio % "test"

As we are planning to run the tests with SBT we have to specify a special test framework in SBT Settings.scala:

testFrameworks := Seq(new TestFramework("zio.test.sbt.ZTestFramework"))

Now we are ready to start writing test scenarios. We will start with functionality, that doesn’t have dependencies on other services. As you remember we have implemented the SubscriptionLogic service. Let’s test it!

We create a LiveSubscriptionLogicSpec.scala object in io.pager.subscription package in test folder.

import zio.test._

object LiveSubscriptionLogicSpec extends DefaultRunnableSpec {

override def spec: ZSpec[Environment, Failure] = suite("LiveSubscriptionLogicSpec")()

}

To start, we import zio.test package. It contains ZIO Test building blocks.

We extend DefaultRunnableSpec trait which is similar to zio.App - it provides ZEnv (Random, Clock etc.) and runs provided scenarios.

To create a spec we use suite method, which has two parameters - suite name and test scenarios.

From now we can run our unit tests by clicking Run button near the class name in IntelliJ IDEA or using sbt test command.

We have defined our first spec. Currently, it is empty, so let’s fix that.

Last time we have implemented SubscriptionLogic.

The main task of it is to handle user subscriptions to GitHub repositories.

As we are writing unit tests we would like to abstract from the database and will store everything in memory.

Fortunately, we already have implemented in-memory versions of ChatStorage and RepositoryVersionStorage.

We start with creating an instance of the service, which we will be used in every scenario:

type RepositoryMap = ULayer[Has[Ref[Map[Name, Option[Version]]]]]

type SubscriptionMap = ULayer[Has[Ref[Map[ChatId, Set[Name]]]]]

private def service(

subscriptionMap: Map[ChatId, Set[Name]] = Map.empty,

repositoryMap: Map[Name, Option[Version]] = Map.empty

): ULayer[Has[SubscriptionLogic.Service]] = {

val chatStorage = Ref.make(subscriptionMap).toLayer >>> ChatStorage.inMemory

val repositoryVersionStorage = Ref.make(repositoryMap).toLayer >>> RepositoryVersionStorage.inMemory

(Logger.silent ++ chatStorage ++ repositoryVersionStorage) >>> SubscriptionLogic.live

}

In order to instantiate the service, we have to provide an initial in-memory state.

It is used to instantiate storage services, which are used in SubscriptionLogic.Live service.

We express the state using Map collection wrapped in zio.Ref.

Then this Ref is converted to ZLayer and provided to inMemory layer recipe.

By default, these maps are empty and do not contain any data.

However, in more advanced test cases we can prepare the state before we write some actual test scenarios.

To keep things simple we replace logger with a dummy instance.

Ideally, we would like to test log messages as well.

We will be clever and will use property-based tests. For that we have to write data generators:

import zio.random.Random

import zio.test.{Gen, Sized}

import zio.test.Gen._

object Generators {

val repositoryName: Gen[Random with Sized, Name] = anyString.map(Name.apply)

val chatId: Gen[Random with Sized, ChatId] = anyLong.map(ChatId.apply)

}

We are reusing generators provided by the framework. Generated values are wrapped into our values classes.

Both generators require Random and Sized instances and ZIO will provide them in ZEnv.

It is time to implement our first test scenario:

override def spec: ZSpec[Environment, Failure] = suite("LiveSubscriptionLogicSpec")(

testM("return empty subscriptions") {

checkM(chatId) { chatId =>

val result =

SubscriptionLogic

.listSubscriptions(chatId)

.provideLayer(service())

assertM(result)(isEmpty)

}

}

)

Let’s take a closer look at what is going on here.

testM builds a test scenario. We label this test and in the body of it, we have an effectful test.

There is also a pure version available - it’s simply test.

checkM provides the test with generated data samples.

It means we don’t have to hardcode chatId value but the framework will generate some random values for us.

If we would need to generate more than one chatId we would have to specify 2 generators:

checkM(chatId, chatId) { (chatId1, chatId2) =>

However, ZIO Test has a limit of 6 generators in one checkM call.

If we would need more than that, we could have several checkM calls inside the test or combine 2 generators into one:

val chatIds: Gen[Random with Sized, (ChatId, ChatId)] = chatId <*> chatId

The “TIE fighter” operator is zip method which will create a tuple of the generators. We can use it in the test:

checkM(chatIds) { (chatId1, chatId2) =>

The scenario itself describes a call to subscription service and compares expected results with actual.

Wait, we don’t have a method listSubscriptions on module level!

Yes, for that we have to create “convenience methods” (or accessor methods) inside the module:

def listSubscriptions(chatId: ChatId): RIO[SubscriptionLogic, Set[Name]] =

ZIO.accessM(_.get.listSubscriptions(chatId))

The method requires a Has[SubscriptionLogic.Service] as environment and when it is provided will return a result.

For every method in Service trait we have to create such an accessor method.

It sounds like a lot of boilerplate.

If you want to be super efficient and want to save a bit of your precious time you can use macros.

For that we mark our module with @accessible annotation:

import zio.macros.accessible

@accessible

object SubscriptionLogic {

This is not mandatory but can help you to save some time writing those accessor methods and clean some of the boilerplate out of your modules. Anyway, it is a bit off topic. Let’s go back to our test scenario.

To compare the results we use assertM method which has two argument lists: the actual value and the expected value.

If we would like to do the same for pure values, we would call assert method.

ZIO provides set of basic assertions: isEmpty, equalTo, isLessThen, contains and many others.

These assertions can be composed into a more complex checks: isRight(isSome(equalTo(1))).

Names of the expectations should give us a hint about what they are doing.

If you would like to learn more please check the Scaladoc.

Provided expectations can be used to build your custom expectations.

Let’s have a look at a test in which we call several methods of the same service:

testM("successfully subscribe to a repository") {

checkM(repositoryName, chatId) {

case (name, chatId) =>

val result = for {

_ <- SubscriptionLogic.subscribe(chatId, name)

repositories <- SubscriptionLogic.listRepositories

subscriptions <- SubscriptionLogic.listSubscriptions(chatId)

subscribers <- SubscriptionLogic.listSubscribers(name)

} yield {

assert(repositories)(equalTo(Map(name -> None))) // there might be something missing here

assert(subscriptions)(equalTo(Set(name))) // and here ...

assert(subscribers)(equalTo(Set(chatId)))

}

result.provideLayer(service())

}

}

We are using accessor methods to call service methods.

Then we check these results using assert methods and provide the service layer.

The biggest trap I have fallen with ZIO Test.

This kind of mistake might happen not only when working with ZIO Test, but with any other effectful code.

I was used to ScalaTest matchers and wrote all the assertions in a column.

However, assertions are values.

ZIO Test assertions do not have side effects.

Do you see where I’m getting?

Assertions won’t throw an exception and abort a test if assertion has failed.

Assertions must be chained together and interpreted by the framework.

It means that in the test above only 1 out of 3 assertions is checked (the last one).

Unfortunately, these mistakes happen and the compiler won’t guard you.

Hopefully, it will change in the future.

That’s definitely not the behavior we would expect. The correct version would be:

...

} yield {

assert(repositories, equalTo(Map(name -> None))) &&

assert(subscriptions, equalTo(Set(name))) &&

assert(subscribers, equalTo(Set(chatId)))

}

The only difference with the original code is the added && (AND) operators.

ZIO Test assertions are combined together using boolean algebra operators.

In other cases, we could use || (OR) operator. Also, we can negate the assertion using ! (exclamation mark).

For those who don’t like symbolic notations, there are named versions of the operators.

Check the code to get a better understanding of the available operations.

To avoid that kind of mistakes I would recommend trying a linter.

Code reviews might also help but these mistakes are quite hard to spot.

In this specific project I have used Wartremover.

It’s a Scala linter, that has a flag NonUnitStatements which will help you to find unused effects at compilation step.

Unfortunately, linters have their own drawbacks.

Wartremover caught quite a lot of false positives. Because of that we have to exclude some of the checks.

You could also try using other linters, that look for non-unit statements, Wartremover is just an example.

Also, if you like experimental stuff you could try ZIO shield.

Fake all the work!

Let’s start with a simple example. This example is taken from ZIO codebase.

testM("expect call for overloaded method") {

val app = random.nextInt

val env = MockRandom.NextInt(value(42))

val out = app.provideLayer(env)

assertM(out)(equalTo(42))

}

Value app is an effect of type ZIO[Random, Nothing, Int].

Random is a required environmental dependency.

In other cases, it might be a resource, for example, a SQL database connection.

Instead of a real Random we are providing a mocked instance MockRandom which should return 42 when we call for nextInt.

Also, if we would have a resource that we would like to share between scenarios, we would provide it once with provideManagedShared method of Spec:

object WithResourceSpec extends DefaultRunnableSpec {

val myExpensiveResource: ULayer[ExpensiveResource] = ZLayer.fromManaged { ... }

override def spec: ZSpec[Environment, Failure] = suite("WithResourceSpec")(

testM("scenario 1") { ... },

testM("scenario 2") { ... }

).provideLayerShared(myExpensiveResource)

}

We create a layer of the resource once and provide it to the whole suite. With that, it will be shared between all test scenarios.

Let’s have a look at more specific and complex test examples.

We have a ReleaseChecker service, which has dependencies on other services.

To be super-efficient we don’t want to build the whole dependency tree for every test case.

We want to test the behavior of ReleaseChecker with different inputs.

In this specific case, the service is requesting inputs from other services.

We would like to fake these services and provide inputs ourselves.

ZIO mocks will be defined outside the specification and outside of our modules. A mock will be located in service test folder having the same package structure as the target service. Inside of a mock object we specify service method definitions:

import zio.test.mock._

import io.pager.subscription.SubscriptionLogic.SubscriptionLogic

object SubscriptionLogicMock extends Mock[SubscriptionLogic] {

object Subscribe extends Effect[(ChatId, Name), Throwable, Unit]

... // skipping the rest

}

SubscriptionLogicMock is extending Mock trait which brings us some mocking capabilities to mock service behaviour.

Above we can see one of the service method definitions.

We make it an object, which extends Effect and specifies method inputs, error type and outputs as type parameters.

All the inputs are gathered in one big tuple. In case if you don’t have an input, it would be just a Unit.

In our case for all the service methods we use Effect as service always returns an effect.

If you have pure methods that are not wrapped into ZIO data type you should use Method type instead of Effect.

Also, there are Stream and Sink types to mock streaming components.

I would prefer to use lowerCase names for method definition objects so they look like normal objects in test scenarios.

Also, even though the official Scala style guide recommends to use UpperCase

notation for objects there is an exception when mimicking a function with an object.

However, I will follow the official ZIO guidelines and use UpperCase.

This will come handy when we will start using macro generated mocks.

When we are done with specifying methods

we have to create a ZLayer recipe for our mock.

It will be used in our test scenarios.

val compose: URLayer[Has[Proxy], SubscriptionLogic] =

ZLayer.fromService { proxy =>

new SubscriptionLogic.Service {

override def subscribe(chatId: ChatId, name: Name): Task[Unit] =

proxy(SubscriptionLogicMock.Subscribe, chatId, name)

... // skipping the rest

Good news! We have mocked the first method in the service.

Unfortunately, there are some bad news as well - we have to implement interaction with the mock instance for every method.

Sounds boring, however, some people say “work smarter, not harder”.

That is why we can write a macro, that will do some work for us.

Fortunately, in our case, we don’t even need to write macros ourselves as it is already done by people from ZIO community.

Like @accessible macro that we saw before.

Another annotation, that we can use to simplify our life is @mockable.

To get rid of the boilerplate using @mockable for a service we should follow the module pattern and mark the mock definition with the annotation:

import zio.test.mock.mockable

@mockable[SubscriptionLogic.Service]

object SubscriptionLogicMock

Aaaand… that’s it!

From now on we can use SubscriptionLogic mocks in our tests.

Remember I said it will come handy to use UpperCase?

The reason is that macro generated code also uses UpperCase and we will have to use it in test scenarios.

Let’s test ReleaseChecker service, which uses SubscriptionLogic.

Also, it has a few other dependencies that we have to mark with the @mockable annotation.

We create a new spec:

object LiveReleaseCheckerSpec extends DefaultRunnableSpec {

override def spec: ZSpec[Environment, Failure] = suite("LiveReleaseCheckerSpec")()

As we remember, ReleaseChecker has one method - scheduleRefresh.

This method is doing all the background work and contains quite a lot of logic:

- it looks for GitHub repositories with subscribers

- takes latest repository versions

- checks for new repository versions

- if there are no new versions it finishes or if there are new versions it updates the version in the storage

- looks for repository subscribers

- notifies subscribers about the new version

Whoah. We could split that into few methods and test them separately.

However, let’s imagine we have a good reason to have such a big method.

In every scenario, we will have to call the same method of ReleaseChecker.

The difference between test scenarios will be only in mock behavior.

We can create a method, which builds the service using mocks and calls the scheduleRefresh method.

We will re-use this method in several tests of the test suite with different mock expectations.

Let’s create a method that will call this method and construct ReleaseChecker service:

private def scheduleRefresh(

gitHubClient: ULayer[GitHubClient],

telegramClient: ULayer[TelegramClient],

subscriptionLogic: ULayer[SubscriptionLogic]

): ZIO[ZEnv, Throwable, TestResult] = {

val layer = (Logger.silent ++ gitHubClient ++ telegramClient ++ subscriptionLogic) >>> ReleaseChecker.live

ReleaseChecker

.scheduleRefresh

.provideLayer(layer)

.as(assertCompletes)

}

Every mock is a ZLayer that can be used to build ReleaseChecker service.

ULayer is an alias to ZLayer, which doesn’t have an environment and doesn’t have an error.

We combine mocked services into a layer and provide it to our Live implementation of ReleaseChecker.

As scheduleRefresh method doesn’t return us anything we say that we expect the test to be successful every time (assertCompletes).

By the way - as is just a map alias, that drops the result of the previous effect.

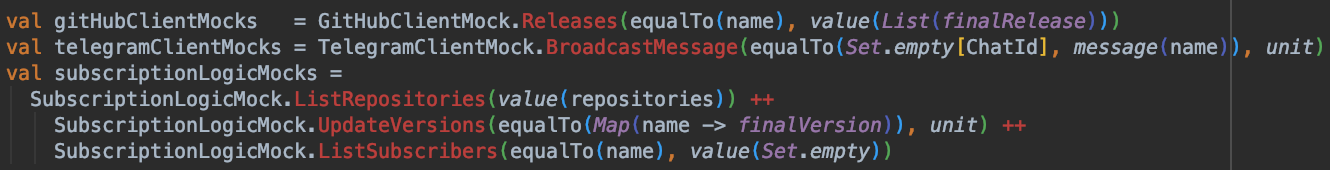

Finally, let’s implement a test scenario with mocked services. Below you can see one of the test scenarios.

testM("Notify users about new release") {

checkM(repositoryName, chatIds) { case (name, (chatId1, chatId2)) =>

val repositories = Map(name -> Some(rcVersion))

val subscribers = Set(chatId1, chatId2)

val gitHubClientMocks = GitHubClientMock.Releases(equalTo(name), value(releases))

val telegramClientMocks = TelegramClientMock.BroadcastMessage(equalTo((subscribers, message(name))), unit)

val subscriptionLogicMocks =

SubscriptionLogicMock.ListRepositories(value(repositories)) ++

SubscriptionLogicMock.UpdateVersions(equalTo(Map(name -> finalVersion)), unit) ++

SubscriptionLogicMock.ListSubscribers(equalTo(name), value(subscribers))

scheduleRefresh(gitHubClientMocks, telegramClientMocks, subscriptionLogicMocks)

}

}

It’s a big example, let’s look at it closely.

val gitHubClientMocks = GitHubClientMock.Releases(equalTo(name), value(releases))

As we don’t want to call a real GitHub service we tell the mock to return us a list of expected releases.

GitHubClientMock.Releases is one of the methods magically generated by macros (or manually written by us if we decided to stay macro-free).

We say that whenever it accepts a value which equals to name we return a pre-defined list of releases.

Looks simple. We just have to get used to the assertions (e.g equalTo) and expectations (e.g value), which are pretty straight-forward.

telegramClientMocks should be simple to understand if you got the idea of gitHubClientMocks.

There are only subscriptionLogicMocks left.

val subscriptionLogicMocks =

SubscriptionLogicMock.ListRepositories(value(repositories)) ++

SubscriptionLogicMock.UpdateVersions(equalTo(Map(name -> finalVersion)), unit) ++

SubscriptionLogicMock.ListSubscribers(equalTo(name), value(subscribers))

Here we have defined several expected calls of the service.

If an expected method wasn’t called, the framework will return us an error that will fail the test.

Also, a test will fail if we have called a method with unexpected arguments.

Basically, the framework gives us the possibility to set strict expectations and tests will fail when something unexpected happens.

As we have several expectations of the mock we must chain these expectations using andThen or symbolic alias ++.

Note, that ++ operation is not associative. This means that we must keep the correct mocked method call order.

If we do not care about the order we can use another operator - &&.

That’s not all, with this operator we can compose expectations from different services together:

val mocks: Expectation[GitHubClient with TelegramClient with SubscriptionLogic] =

GitHubClientMock.Releases(equalTo(name), value(releases)) &&

TelegramClientMock.BroadcastMessage(equalTo((subscribers, message(name))), unit) &&

SubscriptionLogicMock.ListRepositories(value(repositories)) &&

SubscriptionLogicMock.UpdateVersions(equalTo(Map(name -> finalVersion)), unit) &&

SubscriptionLogicMock.ListSubscribers(equalTo(name), value(subscribers))

This gives us an Expectation with all services composed together. What can we do with it? We can convert it to a layer!

For the convenience inside of Expectation there is an implicit for that:

import zio.test.mock.Expectation._

val releaseChecker: ULayer[ReleaseChecker] = (Logger.silent ++ mocks) >>> ReleaseChecker.live

Now we can provide this layer to our service call which requires it and we are done. We have a small and concise scenario that tests a relatively big method.

There are several ReleaseChecker test cases available on GitHub.

You are welcome to review them.

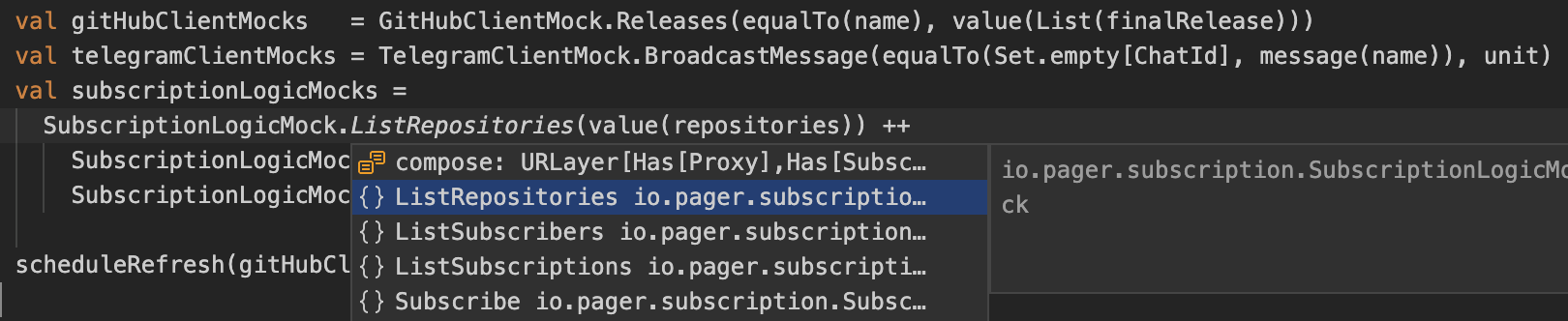

One little issue with mock support in some IDEs

If you are using Metals you are safe and you can skip this part.

However, if you are using IntelliJ IDEA there is a small issue.

Even if you have installed zio-intellij plugin you won’t see all macro generated code and IntelliJ will treat this code as erroneous:

In the meantime, the same code in VSCode with Metals has no errors and auto-complete works fine:

Unfortunately, @mockable annotation is not yet supported by zio-intellij.

Even though other annotations (e.g @accessible) generated code is discoverable.

I have created an issue to support @mockable.

Of course, if you will write mocks manually this issue won’t bother you.

Bonus track

ZIO Test provides users with test aspects. You can think of these aspects like test features or traits. There are some generic features that you would like to use in your tests. Here are some of them:

-

ignore- mark test as ignored -

after- runs an effect after a test -

flaky- retries a test until success -

nonFlaky- repeats a testntimes to ensure it is stable -

jvmOnly- runs a test only on JVM platform - and others.

Aspects can be used both on a scenario level and on a suite level.

import TestAspect._

object LiveReleaseCheckerSpec extends DefaultRunnableSpec {

override def spec: ZSpec[Environment, Failure] = suite("LiveReleaseCheckerSpec")(

testM("Update repository version for the very first time") {

// ... scenario code

} @@ ignore

) @@ nonFlaky

We marked all tests in our suite as nonFlaky and the first test in the suite is marked as ignored.

Be careful, blindly marking all tests as nonFlaky will affect your test performance.

By default, the framework will run the spec for 100 times.

Summary

In this article we have explored ZIO Test and its capabilities, we:

- used building blocks from

zio.testto construct a spec - replaced storage state with an in-memory implementation, which we have constructed in a test

- applied property-based testing and created data generators

- learned how to compare expected results with actual results using

assert - avoided common mistake with effect chaining

- touched resource mocking

- built service call expectations using mocks

- mocked all the service dependencies

- removed all the boilerplate required for service mocking using macros

- saw what issues we can expect from using macros and how to handle them

- added test features using aspects

That’s a lot! The best part of this is that there are more things that you can explore by yourself: resource management (we saw just a little example), ScalaJS support, etc.

Conclusion

I like how the code in ZIO Test is well organized. You can easily find tools that you need to build a test. There are no magical implicit conversions, that you have to remember to import. There are macros in the framework but you are not obliged to use them. You have a choice either to write some boilerplate, that will clutter our code or generate some code with macros. As we have seen not all IDEs support macro generated code (at the moment of writing). As we are working with effects, we always have async runtime and we never use blocking in tests. Tests written with ZIO Test are isolated but can use shared resources without heavy machinery involved. The framework makes sure that resources are closed properly. Finally, there are test aspects, that provide you with ways to add generic test features.

However, there are some things, that can be improved. I would like to underline the fact, that at the moment of writing, ZIO is not yet officially released. There are still some open issues on GitHub. To be fair, there are quite many open issues, but there are only few, that are blockers for the official release.

If you try to use the framework yourself, you could have a feeling that some of the tooling is missing. It might be, that in some exotic use cases you will miss some of the testing framework functionality. But look at it from the other side - you have a chance to get a hands on experience in development of open source framework. This is your opportunity to drive the direction of this specific technological ecosystem.

It really feels that ZIO community is investing a lot to make it easy for new users to onboard and start using the framework. There are many other projects in the ecosystem that are actively developed. I’m happy to continue my journey through it.

If you are interested in getting notifications whenever new article is out - follow me on Twitter. Tune in!